Cambodian Prime Minister, Hun Sen’s authoritarian crackdown has rendered his critics defenceless. His last major blow to the opposition was the dissolution of the main opposition party, the Cambodian National Rescue Party (CNRP).

Media outlets, analysts and international observers have been quick to wag their fingers at Hun Sen. Indeed, his actions has understandably dealt a death knell to Cambodia’s democracy. Hun Sen’s sweeping powers in all branches of governments have led many to consider him a dictator. However, the utter speed of the CNRP’s destruction also calls into question the opposition’s strategy and resolve in posing a challenge to Hun Sen’s rule.

Personalist politics in Cambodia

Politics in Cambodia has always been personalist – the divide between party and its leader is often blurred. For the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP), its leading figure is unmistakably Hun Sen and for the CNRP, its Kem Sokha.

According to Associate Professor of Diplomacy and World Affairs at Occidental College in Los Angeles, Sophal Ear, the voting behaviours of the Cambodian population cultivates the environment for personalist parties to thrive.

“People want to vote for people, not parties. Yet in Cambodia, you can only vote for parties. So, the best way to differentiate your party is to have a leader who stands out. The leader of the party embodies the party,” he said in an email reply to The ASEAN Post.

The Cambodian voting system follows a party list system which inevitably helps concentrate power within the leadership of the party. This in turn helps nurture standout leaders who themselves become inseparable from the parties they represent.

“In the case of Sam Rainsy, he created the Khmer Nation Party, but the name was then hijacked. So, his solution was to create a new party and to use his name to identify that party,” Ear continued, in reference to the now defunct Sam Rainsy Party.

Ear also pointed out another example, the Grassroots Development Party (GDP) which was led by the late Kem Ley, a famous political activist who was assassinated in what many believe to be a politically motivated action.

“GDP is not exactly the most popular party because Kem Ley is dead and the other folks, while known in certain circles, aren't household names.”

Unravelling the opposition

Realistically, any opposition party aimed at incapacitating Hun Sen’s rule faces an uphill battle. But the CNRP seemed up to the task.

“I think the CNRP was an attempt to move away from more personalistic politics and focus on an overarching goal. That iteration of the party did fairly well in the 2013 elections, and in the 2017 commune elections,” Joshua Kurtlantzick, Senior Fellow for Southeast Asia at the New York based Council on Foreign Relations.

This caught the eye of Hun Sen who didn’t take long to dismantle the opposition’s “marriage of convenience.” He attacked the opposition at its heart – its two leaders who were previously heads of their own political organisations prior to joining hands to form the CNRP, Sam Rainsy and Kem Sokha.

Rainsy, then President of the CNRP was hit with defamation lawsuits and charges of treason causing him to flee to France and live in self-imposed exile. He resigned from the CNRP because of a law disallowing those convicted of a crime to hold political positions. His role was then taken over by his deputy, Kem Sokha. Sokha led the CNRP to a “victory” during the communal elections in 2017 – where although the opposition failed to unseat the CPP, it significantly reduced its majority.

Hun Sen, who was determined to halt the opposition’s triumphant inroads into the hearts and minds of the people, proceeded to dismantle the CNRP. His first step, attack the personality behind the party.

In the wee hours of September 3, 2017, approximately 200 armed policemen raided his house and hauled Kem Sokha away to a detention facility at the Cambodia-Vietnam border. He was not granted bail and continues to languish in prison on trumped up charges of treason that could see him face 30 years if found guilty.

Hereafter, CNRP was leaderless and fell to disarray. Opposition lawmakers fearing arrest, fled the country in droves.

A flurry of laws was passed throughout the year – the latest being in October – which ultimately allowed the government to submit an application to the courts to disband the opposition. Given that the courts are under Hun Sen’s thumb, it was mere formality and before long, the CNRP was no more.

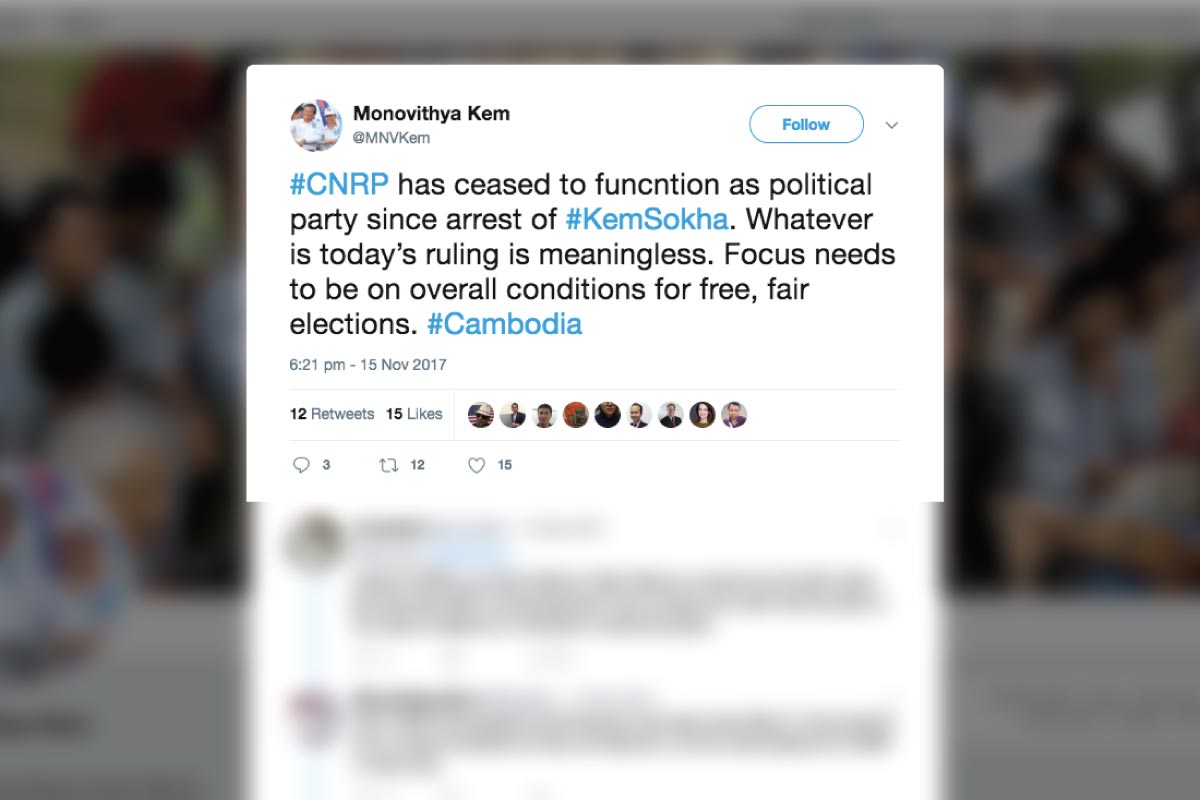

Kem Monovithya, daughter of Kem Sokha and member of the CNRP Permanent Committee in a tweet soon after the CNRP was disbanded admitted that “The CNRP had ceased to function as a political party” since Kem Sokha’s arrest, adding that, the ruling to dissolve the party was hence “meaningless.”

Pol Ham, Deputy President of CNRP even conceded defeat and revealed to the Phnom Penh Post that “It is good if they dissolve the party since I also want to retire… I want to go to the pagoda since I am old now.”

In retrospect, if anyone stood up against Hun Sen, he or she risks the fate that befell Kem Sokha, or Sam Rainsy or any other critic of the longstanding premier. However, in the interest of the Cambodian people, their political needs must be looked into. Given CNRP’s gains, there seems to be rumblings of dissatisfaction over Hun Sen’s leadership and an effective opposition must exist to address this.

When asked if Cambodian politics in the long run would be better off if the masses started shifting away from personalist parties and opt for or create parties that are more ideological in nature, Ear, who is also a policy analyst admitted that in theory, the answer is yes.

“But the problem is the same idea that corporations aren't people and parties aren't people. Of course, there are people behind both corporations and parties, but you need charismatic leaders to inspire people to believe in the impossible,” he added.

The key to a prosperous opposition seems to lie in a balance between personality and ideology. Will Cambodia find that balance before its too late?

Recommended stories: