The RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership) rose to prominence soon after US President Donald Trump rescinded his commitment to the TPP (Trans-Pacific Partnership) trade deal earlier this year.

The TPP aimed to establish a regional FTA (Free Trade Agreement) and focussed on liberalising trade in goods and services, investment, intellectual property rights, environmental protection, labour, financial services, technical barriers to trade and other regulatory issues.

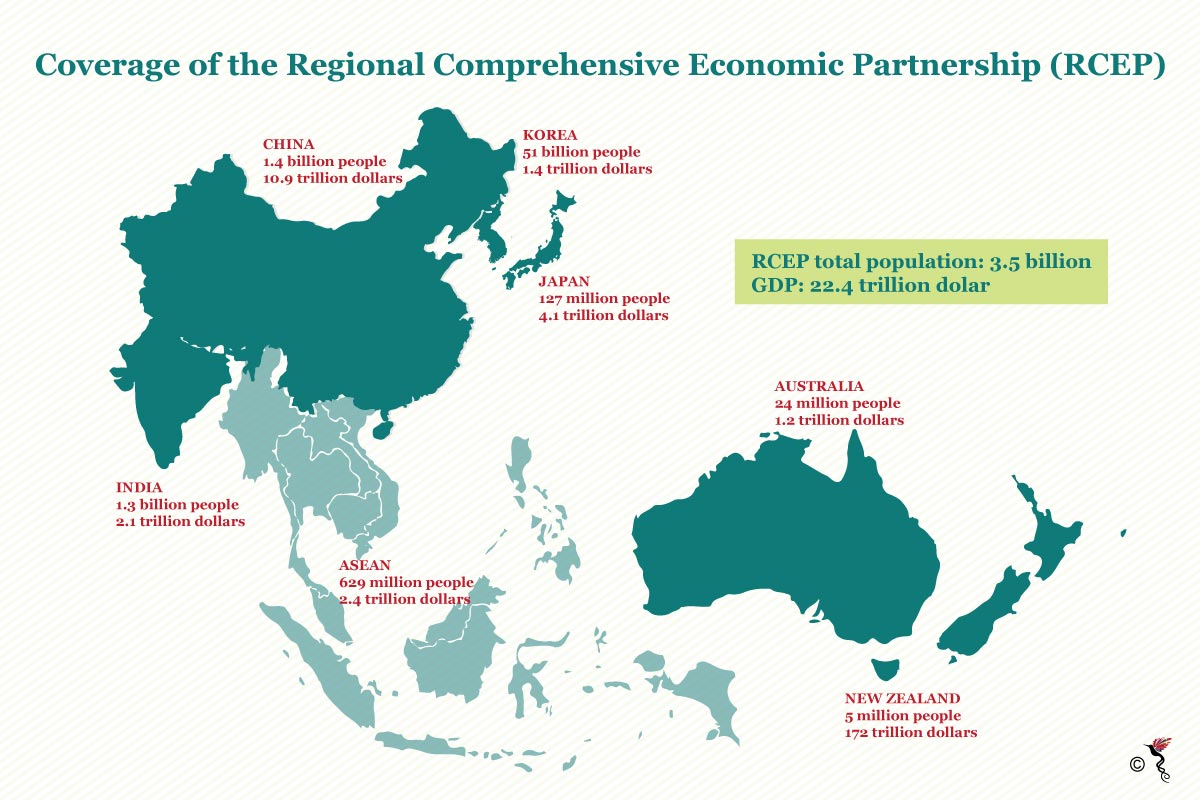

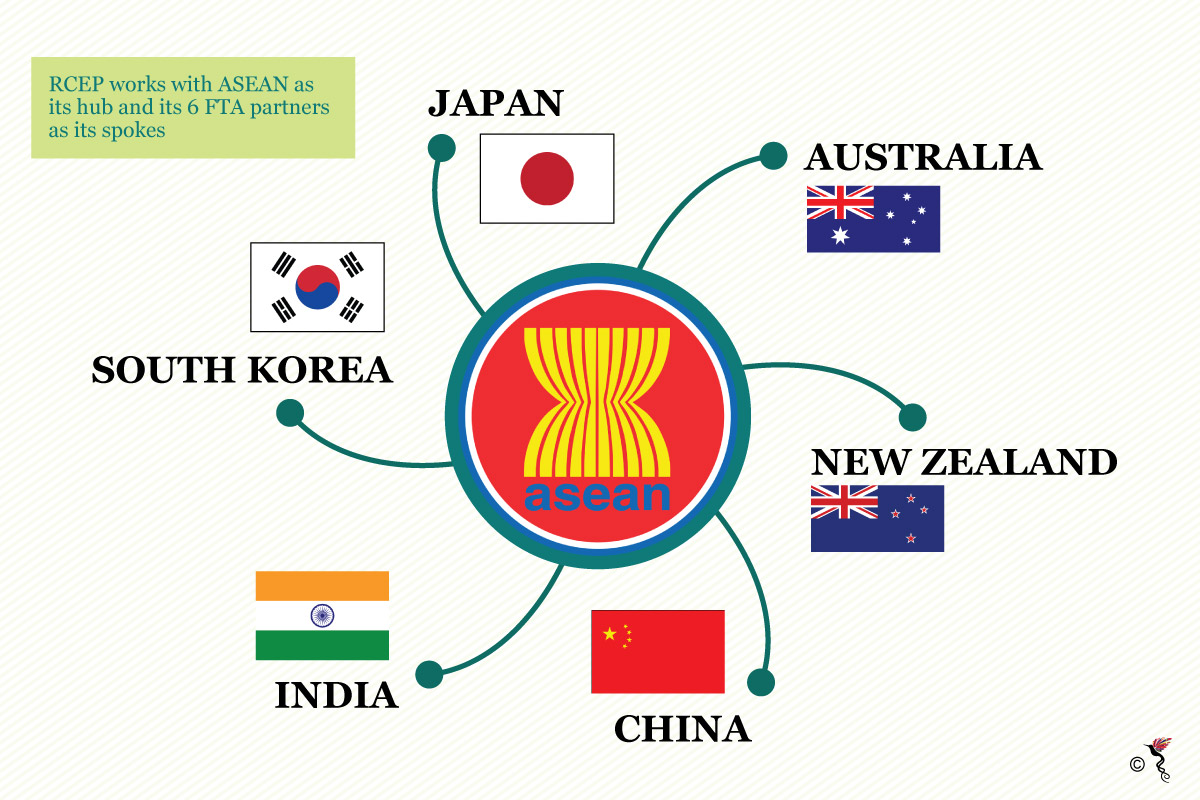

Opposingly, the RCEP aims to deepen existing FTA cooperation between ASEAN and its six existing FTA partners (China, South Korea, Japan, India, Australia and New Zealand) to form an integrated regional economic agreement.

The coverage of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.

It is important to note that China has been glaringly excluded from the TPP, but the Asian giant plays an important role in RCEP. When Trump signed the Executive Order marking the official withdrawal of the largest economy from the TPP trade deal, many have begun to treat both treaties as if they had been in competition with one another.

The analysis that ensued had a markedly similar undertone. Now that the US has withdrawn from the TPP, China looks determine to supplant it with the RCEP – irrevocably replacing the US as the economic superpower of the region.

It is a reasonable assessment to make. However, predicating that analysis on the fact that the RCEP is led by China, hence Beijing’s leadership is a motivating factor towards wanting a swift conclusion to negotiating the treaty is a faulty assumption to make.

The main reason for that is because the RCEP is inherently ASEAN-led. RCEP represents an effort by the 10-member association to deepen its economic relations within its membership, with its existing FTA partners and between the FTA partners. In a sense, ASEAN is at the hub of the deal and its six FTA partners are at its spokes.

What keeps the wheel intact is ASEAN’s centrality in its ability to weigh between the interests of more competitive powers like China and Japan. The composition of economies within the RCEP is enough to show that there is adequate balance to “Chinese supremacy” in the involvement of India, Japan and Australia.

The hub and spokes representation of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership trade deal.

Nevertheless, the perception that China will use the RCEP to its advantage by filling the void left by the US does not lie with its supposed leadership of the trade deal. Instead, it lies in how the RCEP can be used as a means for Beijing to achieve its grandiose vision for a wider development strategy – the BRI (Belt Road Initiative).

The BRI covers 65 percent of the global population, 75 percent of global energy resources and 40 percent of the world’s GDP (Gross Domestic Product). It spans 65 countries across three continents, primarily Asia, Europe and Africa. Beijing’s annual trade with countries involved with this initiative is already in excess of 1.4 trillion dollars. Estimates by Credit Suisse reveal that China could invest upwards of 500 billion dollars into 62 BRI projects in the upcoming five years.

RCEP’s completion would grant preferential access to the markets of each country and this is key towards China’s ambitions with the BRI. For example, the Chinese construction industry can take advantage of this partnership given that there would be demand for construction supplies like cement and steel for the completion of projects under the initiative. It also opens the opportunity for Beijing to address its excess capacity within such industries. This is especially important since one of the fundamentals of the BRI is infrastructure development and China has already embarked on ambitious development projects around the region.

Washington’s absence from the TPP has yet to kill the treaty. The remaining 11 countries are going through with it and are looking to ink a deal by November this year.

According to Resident Senior Fellow at the Institute of China American Studies, Sourabh Gupta, if the deadline is to arrive at a framework agreement or an agreement on principles and not specific details of the deal, it is an achievable feat. However, with the US out of the agreement, it would be an uphill battle for the other 11 countries.

“The deal that the 11 countries reach will be more diluted than a TPP agreement that would have involved the US. Some of the hardest concessions that TPP members made, were made to the US in exchange for tariff free entry to the US market. Now with the US dropping out of the deal, some of these concessions by Vietnam, Japan, etc. will be dropped from the TPP-11 agreement,” he said.

Hence for those who fear that the RCEP will facilitate the BRI which would cement “Chinese hegemony” within the region, an invigorated TPP-11 would serve as a form of balance to Beijing’s overreach. Nevertheless, knowing that it is ASEAN pulling the wagon of the RCEP, perhaps solace can also be found there.