The handful of plantation companies present in Seruyan before Darwan arrived on the scene had stoked simmering resentment. Villagers claimed the first they knew their land fell inside a license issued to PT Agro Indomas, near Lake Sembuluh, was when their farms were torched or bulldozed. Owned by a pair of Sri Lankan billionaires, the company desecrated their graveyards, prompting villagers to destroy a bridge inside the concession.

A man whose land was taken by a company called PT Mustika Sembuluh later told an NGO that people had been offered no choice but to accept compensation on the company’s terms in what was viewed as a “forceful” land transfer. “If we resisted, we faced the security apparatus brought in to guard the company’s operations,” he said. “Our village chief told us back then that if anyone refused to give up the land the company would proceed to clear those lands anyway because they had the permit, and because our lands are state land anyway.”

The plantations polluted the lake and rivers to the point that drinking water in some areas had to be brought in by tanker truck. It also dried up the fishing trade, which along with the collapse of shipbuilding fuelled a “tremendous outmigration” of men, said Gregory Acciaioli, a University of Western Australia lecturer who did fieldwork in the district. “There were an enormous number of female head of households who were working, filling polybags with soil and seedlings for the oil palm plantations,” he told us. “They were barely scraping by.” He added, “It was a pretty depressed situation.”

Despite these experiences there was a new optimism about large plantations early on in Darwan’s reign, according to Mashudi Noorsalim, a researcher who has studied the growth of Seruyan’s oil palm industry. When Darwan took office, some were bullish about the prospect of employment, or of earning contracts to transport fruit or build access roads. Noorsalim told us that many residents thought things would improve because Darwan, the man shepherding in a new wave of investment, was a son of the soil. “Some of the people believed he would make the plantations help them,” he said.

As a bupati, Darwan could give licenses to whomever he wanted, without public consultation or bidding. The Ministry of Forestry theoretically exercised control over a late stage of the permitting process in areas of land that fell under its extensive jurisdiction. But across Central Kalimantan province the ministry was mostly ignored, removing the final check on the bupatis’ permitting powers. In Seruyan, this led to a boom in plantation licenses that exceeded almost every other district in Indonesia.

“Some of the people believed Darwan would make the plantations help them”

Our analysis of permits from government databases and other sources shows that between 1998 and 2003, only three licenses were awarded to oil palm companies in Seruyan. In 2004 and 2005, Darwan issued 37, collectively covering an area of almost half-a-million hectares, more than 80 times the size of Manhattan. This matched a similar pattern across Kalimantan, albeit on a larger scale, as bupatis took advantage of their control over land deals, handing out a flurry of licenses that led to an explosion in deforestation.

Plantation licenses were issued over most of Seruyan, including inside Tanjung Puting National Park.

Among the first to get a license from Darwan was the BEST Group, a company privately owned by the Indonesian Tjajadi brothers. In a brazen disregard for the law, Darwan gave them a license that overlapped with Tanjung Puting. The national park had received a stay of execution in 2003, when Jakarta finally took action against the illegal logging ravaging its interior. Security forces descended on the park in a display of power intended to signal that the heyday of uncontrolled timber extraction was over.

The Ministry of Forestry pressed Darwan to revoke the permit. But in a signal of where the real power lay in this new dawn, he stood firm, and BEST ploughed its bulldozers into the protected forest.

A sign erected by the BEST Group, left, reads, “If you want to succeed, get out of your comfort zone.” Another sign depicts company employees interacting with orangutans: “They need us to protect them.”

In 2005, Arif Rachmat became CEO of his family’s agribusiness arm, Triputra Agro Persada, and clearing began in one of its first ventures, a giant concession south of Lake Sembuluh. Two of Indonesia’s wealthiest families were brought together under the corporate structure that owned his firm’s plantations in Seruyan.

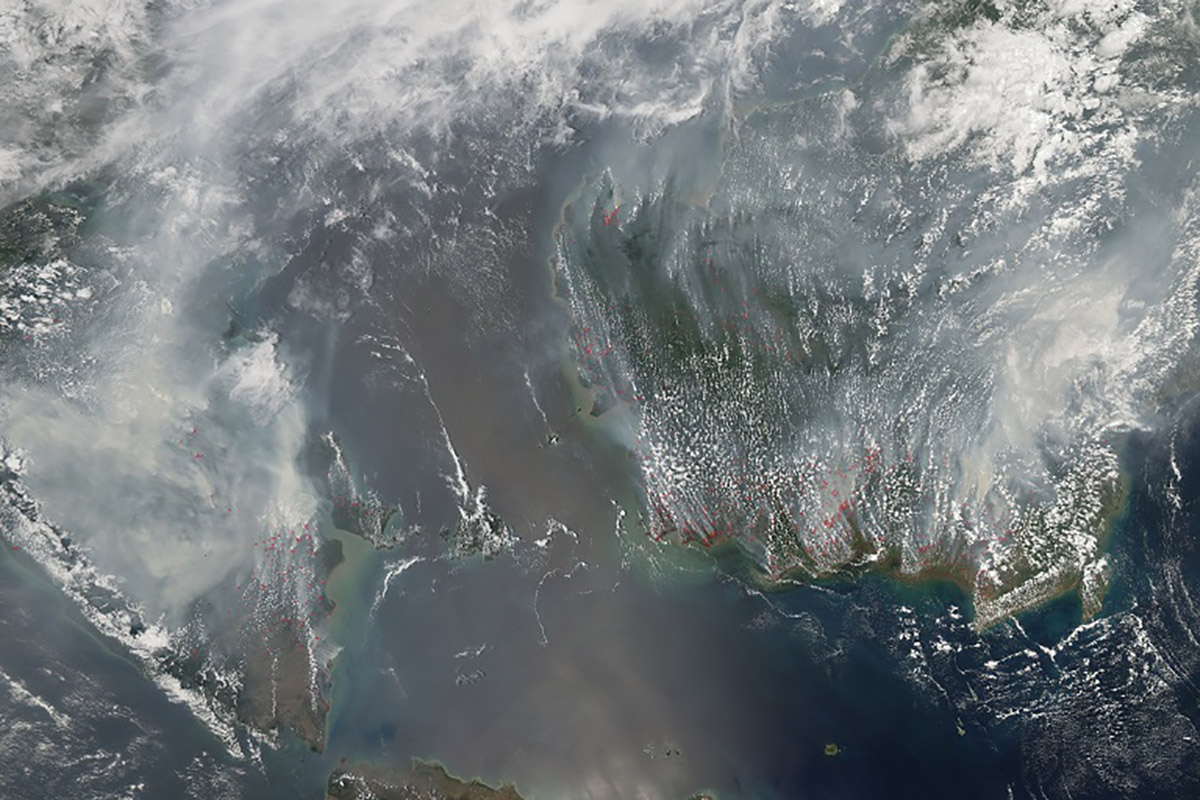

Borneo’s forests held immense volumes of carbon that were released when they were cleared for plantations. In the island’s southern stretches much of this jungle grew on peat bogs, composed of deep layers of organic matter built up over thousands of years. To plant on peat, oil palm growers dug vast trenches to drain it of water. This made it rapidly decompose, releasing powerful greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. The dried peat was also highly flammable. Both companies and farmers had a habit of using fire to clear land for agriculture. In 2006, Indonesia experienced one of the worst burning seasons in memory, as smoke from fires across Sumatra and Kalimantan set off a carbon bomb and blanketed the region in haze visible from space. Under Darwan’s watch, Seruyan was among the worst-affected areas.

Fires on Borneo and Sumatra in September and October 2006. Photo: NASA

In a 2007 documentary on the impact of palm oil in Seruyan, a villager points to a few tall trees left standing in a denuded landscape. At the crest of one sits a huge orangutan. The primates relied on the expanse of forest that stretched across Seruyan’s southern reaches for their habitat. They could survive the loss of some of the largest trees to loggers, but not the outright flattening of their home for plantations.

Tanjung Puting National Park contains one of the the largest and most concentrated populations of orangutans left in the wild.

The same year that Seruyan went up in flames, a report commissioned by the British government drew attention to the scale of emissions from global deforestation, which had become more significant even than the fossil-fuel guzzling transport sector. In 2007, the World Bank arrived at the startling conclusion that due to the destruction of its jungles and peatlands, Indonesia was producing more greenhouse gas emissions than any nation but the U.S. and China.

Deforestation and changes in land use – a euphemism for the advance of plantations – accounted for some 85 percent of Indonesia’s emissions. Globally, the country accounted for more than a third of emissions within this category, now recognised as a primary driver of climate change.

Due to the destruction of its jungles and peatlands, Indonesia was producing more greenhouse gas emissions than any nation but the U.S. and China.

The majority of forest loss in the archipelago was occurring on the islands of Sumatra and Borneo, which bore the brunt of the plantation growth. But even there, the destruction was concentrated in just two provinces: Riau on the east coast of Sumatra, and Central Kalimantan, home to Darwan Ali. The region had become central to a global crisis, and Seruyan was playing its part. – to be continued.

Photos by Leo Plunkett, Sandy Watt, Tom Johnson and Sam Lawson. All other illustrations by Sophie Standing.

This article was curated jointly by the environmental news website Mongabay and The Gecko Project, an investigative journalism initiative established by Earthsight. The article is part of an investigative series entitled Indonesia for Sale.

Recommended stories: