“We were all together but suddenly they started firing. I could not look back, because I thought I would die,” 12-year-old Jamal Hussein recounted to an AFP reporter at a refugee camp in Bahukhali, Bangladesh. He has not seen his parents since his five brothers were gunned down by Myanmar’s army (also known as the Tatmadaw) in a massacre at Aung Sit Pyin located in the northern Rakhine state on the August 25, 2017.

The Rohingya is a Muslim group living as a minority in the Buddhist majority Myanmar. Trouble for the Rohingyas, who are often described as “the world’s most persecuted minority”, began when the junta seised power in 1962. Before 1962, the Rohingya people were officially recognised as an indigenous ethnic group in Burma (present day Myanmar) and had even elected as one of the nation’s first female members of parliament, Zura Begum in 1956.

In 1974, the Burmese state categorised the Rohingya people as “foreigners”. When the controversial 1982 Burmese citizenship law was enacted, they were stripped of their nationality which rendered them stateless unless they have the necessary paperwork proving that they have ancestors who lived in pre-independence Burma. Until today, the government refuses to acknowledge them as “Rohingya” which would be akin to legitimising them as an ethnicity, instead, preferring to address them as Bengali immigrants from Bangladesh.

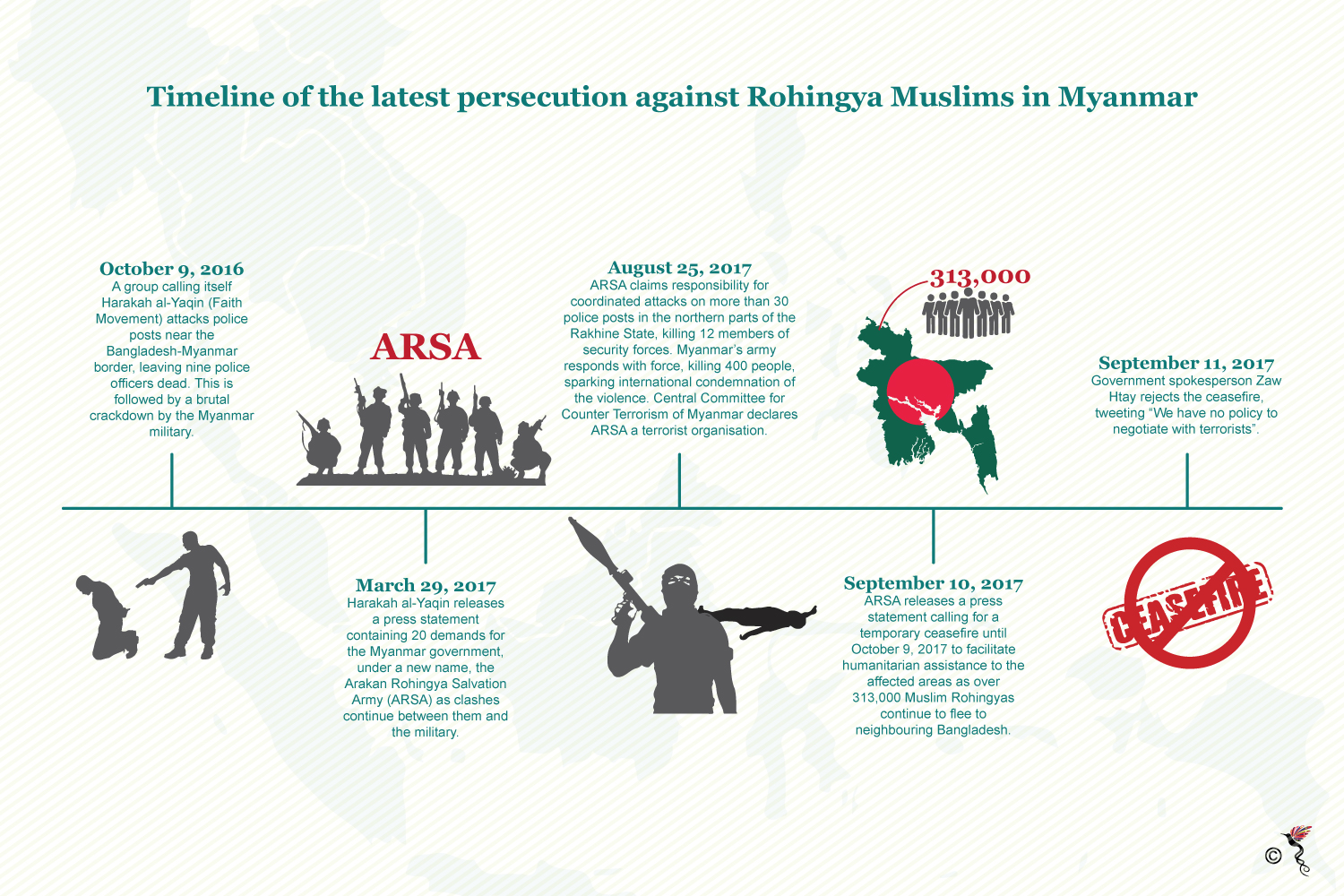

The recent mass exodus of the Rohingyas was prompted by an attack by the ARSA (Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army) on security outposts in the Maungdaw, Buthidaung and Rathedaung townships in the Rakhine state. The ARSA has also been responsible for previous acts of violence which they claimed to be motivated by the repression caused by the junta government. So far, 313,000 Rohingyas have fled the Rakhine State to neighbouring Bangladesh in order to escape the violence.

Timeline of the recent prosecution of the Rohingya

The actions of the ARSA have been met by brutal force from the Tatmadaw. According to a report by the OHCHR (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights), testimonies from survivors of the military crackdown revealed that the army committed serious human rights violations including arson, sexual violence and extrajudicial killings.

The ARSA which defiantly claims it is not affiliated to other terrorist organisations (a claim refuted by Myanmar) has called for a ceasefire in the Rakhine State to facilitate the flow of humanitarian aid into the affected areas. However, government spokesperson, Zaw Htay rejected the notion on grounds that his government does not negotiate with terrorists.

In light of the humanitarian crisis, international observers have condemned Myanmar’s de facto leader and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Aung San Suu Kyi for her inaction with many calling for her to be stripped of her Nobel Prize. The situation has also raised questions on ASEAN’s (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) strict adherence to the principle of non-interference which justifies the organisation’s reticence towards the situation.

The surge of refugees over the Bangladeshi border has prompted Dhaka to propose the creation of internationally controlled “safe zones” to prevent the influx of Rohingyas into the country. However, the proposition has fallen onto deaf ears as the Myanmar government considers the Rohingya people as illegal Bangladeshi immigrants. Hence, a reluctant Bangladesh is forced into housing the refugees temporarily near Cox’s Bazar where most refugees are already located at.

The Rohingyas have continually been persecuted for the past decades and it is unlikely that their situation would change soon. The scale of humanitarian violence if monumental, with many considering it a genocide.

In a letter to the AFP (Agence France-Presse), the Dalai Lama was the latest in a string of Nobel Peace Prize laureates to call on Syu Kyi to find a peaceful end to the crisis.

“As a fellow Buddhist and Nobel laureate I am appealing to you and your colleagues once more to find a lasting and humane solution to this festering problem”, he wrote.

A sobering reminder that violence on innocent civilians should never be the accepted norm of any society or nation regardless of ethnic, religious or cultural affiliation.