The coming together of 10 countries into a single association bound by principles of non-interference and mutual respect is no easy feat. Yet, for the past 50 years, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has left critics flustered. Some predicted that the association will falter into nothingness at the end of the Cold War but it has remained resilient and its agenda has evolved to face the challenges of the new century.

ASEAN’s evolution however, has placed a lot of importance on economic integration with the ultimate aim of creating a single market within the region. The steps to achieve that bold ambition aren’t limited to the boardrooms of high-level intergovernmental meetings but also depend on the cohesiveness of the ASEAN citizenry.

Back to basics: Putnam’s social capital

For there to truly be an ASEAN Community, both the economic and social aspects of integration must be taken into account. The arguments and steps taken towards economic integration have been well fleshed out – given ASEAN’s participation in free trade deals and eschewing of economic protectionism.

But social integration – like Rome – cannot be built in a day. The process is long and arduous and is often beset by hostilities towards others from different national backgrounds. Historical animosity and a rise of negative perceptions towards migrant workers resulting from the pushback from globalisation are some areas that the association must deal with in order to form a more societal ASEAN. Key to this endeavour is to fall back onto the notion of a fluid Southeast Asian culture which breaks the barriers of national narratives of history and embraces a notion of a shared ASEAN culture.

A vital ingredient to social integration is social capital, popularised by Robert Putnam, a distinguished political scientist at the Harvard University John F. Kennedy School of Government. Although there isn’t a singular definition of the term, Putnam’s thesis provides a good basis to then predicate the agenda of ASEAN’s social integration.

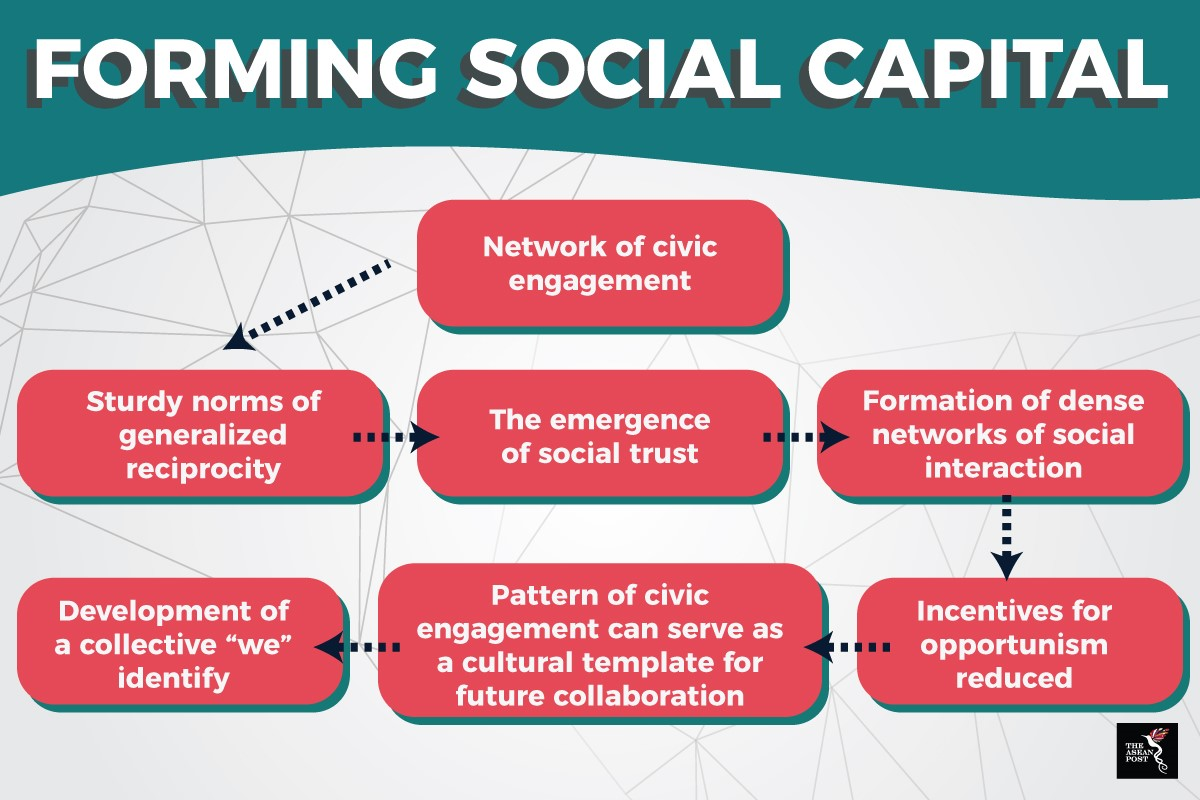

According to Putnam, the first step is the formation of “networks of civic engagement” which would then foster repeated patterns of interaction leading to the emergence of “social trust.” The enmeshment of economic and political negotiation in such networks would significantly reduce incentives for opportunism. Concurrently, the success of past engagements will serve as a cultural template for future collaboration.

“Finally, dense networks of interaction probably broaden the participants' sense of self, developing the "I" into the "we”,” Putnam concludes.

Source: Putnam RD. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster; 2000.

Becoming an ASEAN citizen

Developing the “we” sentiment amongst ASEAN citizens may be difficult but not far-fetched. At the crux of achieving a socially integrated association, is – most importantly – the formation of civic engagement networks as Putnam purported.

The ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community (ASCC) is one of the three main pillars that make up the ASEAN Community. It sets out a vision for a “people centred ASEAN.” This is a good starting point that addresses the need for people within ASEAN member states to better engage amongst each other and build a community that would ultimately benefit its people.

“The people of the region would only believe in ASEAN if they truly feel that they are benefitting from the Community we are building for them. Therefore, we need to convey more effectively to ASEAN citizens the benefits of ASEAN Community,” said Vongthep Arthakaivalvatee, Deputy Secretary-General of ASEAN for the ASCC at an event in Jakarta last August.

Besides that, youth engagement should be at the cornerstone of achieving the vision set out for the ASCC. In a 2014 survey measuring attitudes towards ASEAN amongst the region’s university students, over 80% considered themselves as “citizens of ASEAN.” Furthermore, a majority of the respondents perceived ASEAN members as similar culturally but economically and politically different.

Already, steps have been taken in the right direction with the plethora of university-level engagements across the region like Model United Nation (MUN) Conferences and Student Leadership Symposiums. One such example is the ASEAN Youth Engagement Summit held this year in the Philippines. Attended by organisations representing the interests of youths and young professionals, it is a good starting point for ASEAN to embark upon as the region sets its sights on a more tight-knit ASEAN Community.

Suffice to say that the younger generation in ASEAN seem to be moving in the right direction vis-à-vis regional social integration. Regardless of national boundaries, citizens across the ASEAN region share historical ties that bind their cultures together.

The way forward is not to be coddled by constructions of national identities alone but to look towards developing a regional identity as well.