The Belt Road Initiative (BRI) is an ambition that undoubtedly turns heads and raises eyebrows – but for vastly different reasons.

Plans are already underway – ports, roads, rail infrastructure, oil and gas pipelines, fibre optics networks – and slowly, China’s estimated five trillion-dollar ambition is taking shape. Amid the clanging of the gears of industry propelling this initiative forward, the Southeast Asian region will particularly be under the radar as many countries in the region are part of this extensive network.

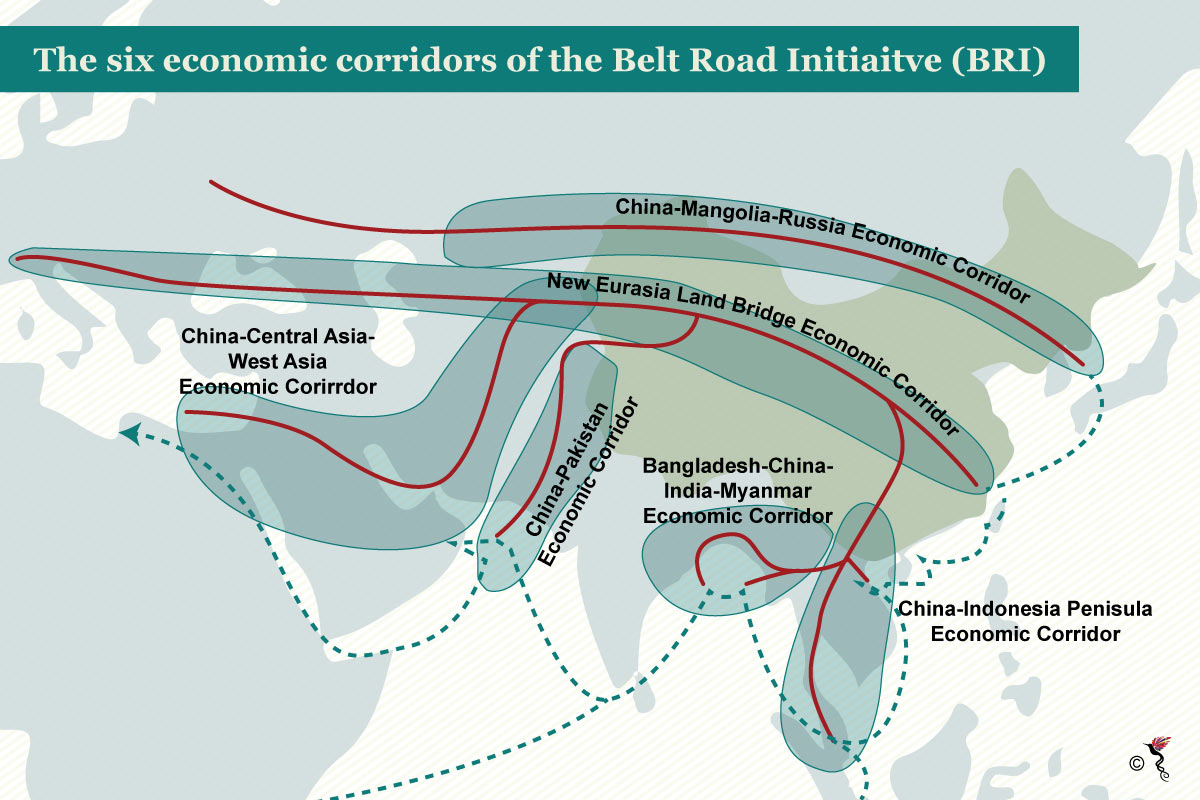

The vast network of the Belt Road Initiative (BRI)

Chinese investments in ASEAN

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has its own developmental plans like the ASEAN Community Vision 2025, Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity 2025 and the ASEAN Economic Community 2025 that gel perfectly with China’s BRI objectives. Estimates by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development reveal that the region would need infrastructure investment anywhere between 60 to 146 billion dollars per year until 2025.

And China is quick to pounce at that opportunity.

Already, railroad projects connecting China to ASEAN member states have either commenced or are being planned. The five-year 5.9-billion-dollar China-Lao-Thailand railway is already 13.5 percent completed after construction began earlier this year. China is also funding major projects like the Indonesia's Jakarta-Bandung High Speed Rail link, Malaysia's East Coast Rail and China-Thai high speed railway.

In addressing ASEAN’s development gaps, China’s investments are, undoubtedly, a welcome proposition. This comes at a time in a highly unusual period in history, where the US advances protectionist policies and China is being heralded as the voice of free market neo-liberalism.

“Trump’s "America First" approach means that he is happy to embrace Chinese trade expansion so long it does not directly affect America's prosperity. Likewise, Chinese leaders are ok with American criticism so long as the U.S. domestic markets continue to buy and import cheap Chinese goods for sale in the country,” Benjamin Ho, Associate Research Fellow at the China Programme, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) told the ASEAN Post.

So, it makes good sense then for ASEAN members to hedge their bets – rely on China for economic gains while turning to the US for a security guarantee. However, as much as the economic benefits are touted, China’s motives – as would the motive of any investor be – is good dividends and this is where China’s intentions with its expansionist policies are called into question.

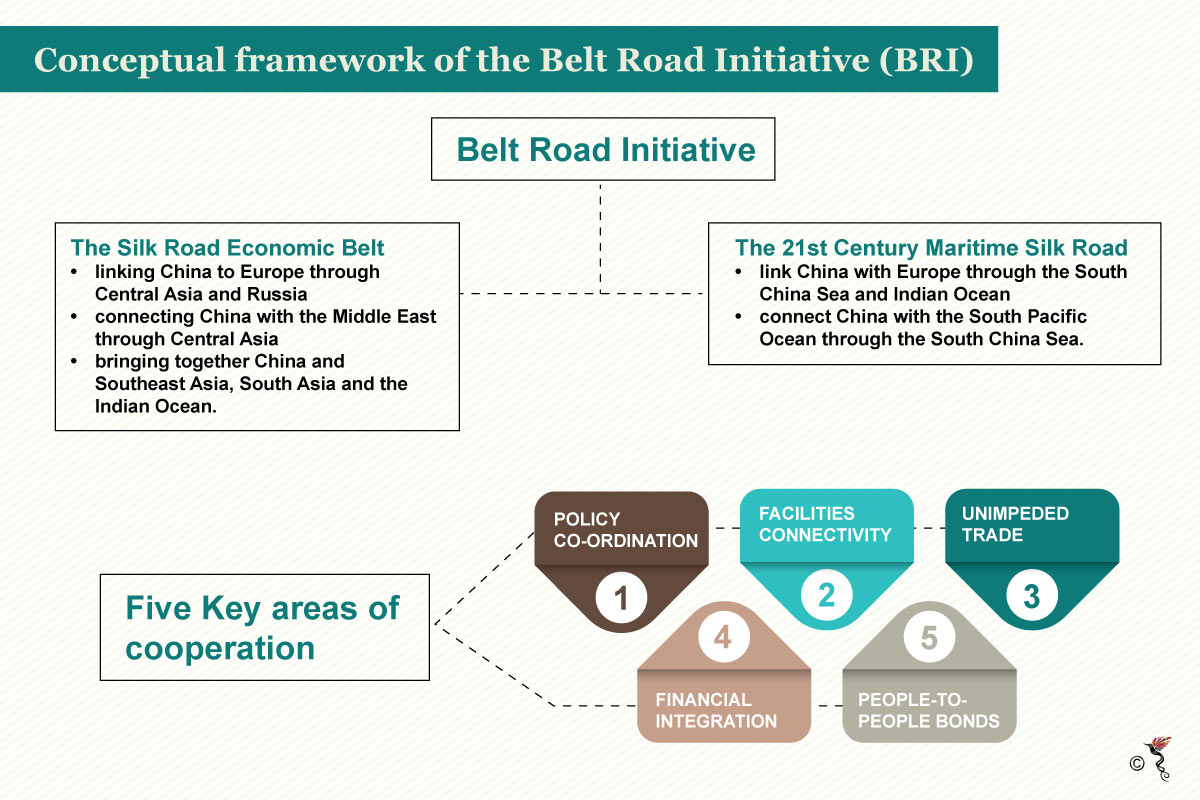

Conceptual framework of the Belt Road Initiative.

Maintaining ASEAN centrality

However, regardless of whether Beijing is looking for monetary gain or loyalty, ASEAN as an organisation, must adapt to this new geopolitical reality by balancing between regional security interests with the US and economic ones with China. To achieve that, ASEAN should hold dear to its principle of centrality.

The concept, as it was once illustrated by prominent Singaporean diplomat, Bilahari Kausikan is a fluid one.

“Centrality is a shape-shifting concept, capable of continual adaptation,” he told a room full of diplomats, journalists and industry leaders at a conference in Singapore early October.

“ASEAN will lose "centrality" only if it loses confidence in its ability to make the painful and difficult adjustments that become more urgent by the day.”

Kausikan’s warning is apt to the shifting geopolitical ground beneath the region’s feet. The domestic pushback from accepting Chinese investments are plentiful as seen in countries like Malaysia, Indonesia and Cambodia. But such investments should not be taken lock, stock and barrel as a sign of pivot towards China. With the exception of Cambodia, every other ASEAN member state has been relatively successful in pleasing both China and the US.

In cases where there is a potential for either major power to exploit ASEAN’s fractiousness, ASEAN would then have to rely on its institutions. At the very least, institutions like the ASEAN Regional Forum and East Asia Summit would play a stifling role and help pull the handbrake on issue that threaten to get out of hand.

“A more unified entity ASEAN would have more leverage both politically as well as economically. It would require stronger ASEAN institutions but without ASEAN I think we would see a more unstable region and very much weaker individual states dominated by China,” Niklas Swanström, Director of the Swedish based Institute for Security and Development Policy told The ASEAN Post.

ASEAN’s strength is in its numbers and its member states can capitalise on that to ensure they get the best of both worlds – infrastructure investment without getting on the bad side of any major power.

Recommended stories: