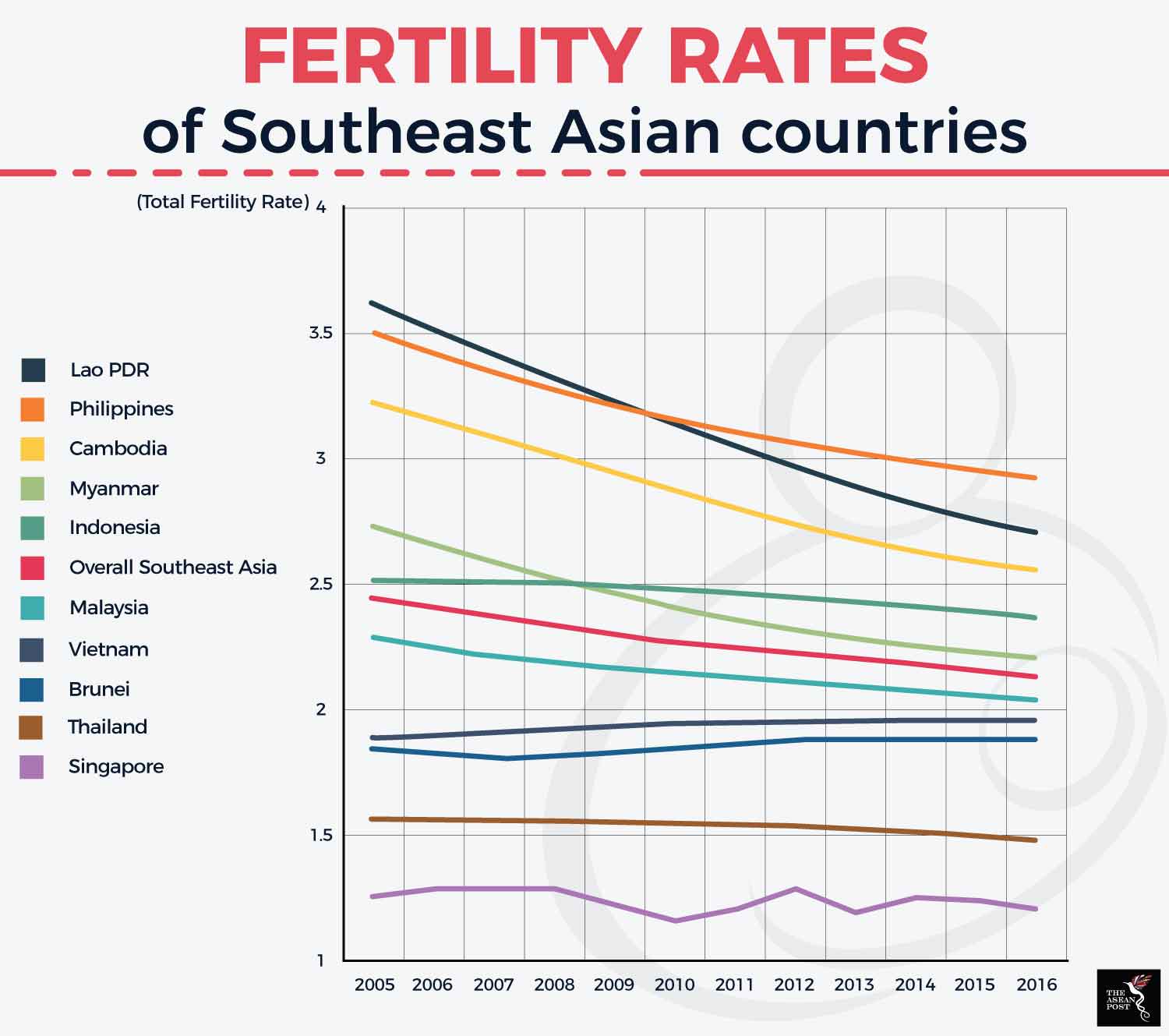

The Southeast Asian region is only just managing to maintain its population but there are indications that the fertility rates of ASEAN member nations are continuing to fall. In 2016, half of ASEAN member countries recorded total fertility rates (TFR) that were indicative of potentially shrinking populations, while two other countries recorded more than 15 percent TFR reduction over the last decade.

TFR refers to the total number of children born or are likely to be born to a woman in her lifetime if she were subject to the prevailing rate of age-specific fertility in a particular population. On average, ASEAN registered a TFR of 2.13 in 2016, just slightly over the 2.1 TFR needed for a stable population. However, between 2007 to 2016, the collective TFR for ASEAN dropped by 10 percent. In 2016, the ASEAN country that logged the lowest TFR was Singapore at 1.2, followed by Thailand at 1.48, Brunei at 1.87, Vietnam at 1.95, and Malaysia at 2.03. At the same time, the TFRs of Cambodia and Lao PDR plummeted 16.7 and 20.6 percent respectively, over the decade.

While to some extent, a declining population could be good for an over-populated world, the negative implications on the region are many. For example, the Philippines’ youth population makes it a fertile ground for foreign investments. Coupled with life expectancy increase, a low TFR is pushing the region towards becoming an aging population. This will result in institutional, economic and social issues related to healthcare for the elderly, the traditional role of women as caretakers and the impact it has on the labour force.

Source: World Bank.

In Singapore, the population building strategy is two-pronged – a combo of moderate immigration to supplement the deficit, government-sponsored packages consisting of housing, childcare, healthcare and reproductive assistance, and the development of more family-friendly labour practices. In 2017, Singapore granted 22,076 new citizenships, which is about the same in previous years. The island nation granted 31,849 permanent residencies in the same year. Many of its Permanent Residents usually take up citizenship eventually.

Regulating reproduction activities

Countries facing a fertility conundrum may also look east to China for inspiration. The country known for its one-child policy implemented between 1979-2015 is quickly moving beyond a voluntary two-child policy to one where every couple is required to have two children. According to a statement by the Population Research Institute (PRI) President, Steven Mosher, besides an about face promotion to reversing China’s birth rate by the state-controlled media in recent months, the 2-children quota strategy is also being pushed to the masses through the communist party mechanism.

“The authorities in Yichang, a city of four million people, have called on all Communist Party members to “take the lead in responding to the Party Central Committee’s call” to have a second child. Younger Party members were advised to lead by example (the Chinese phrase used literally means “doing it starts with me”), while older comrades were told to “educate and supervise their children” with the obvious intent of encouraging grandchildren. Party members of all ages were urged to “take various measures to mobilise the masses to actively achieve a ‘full two children policy’.

“With provincial and local Party committees “mobilising the masses” to reproduce, can even more coercive measures be far behind? To enforce the one-child policy, the Chinese Communist Party forcibly aborted and sterilised hundreds of millions of women over the years. To enforce a mandatory two-child policy, what would the Party not do?”, said Mosher.

The ASEAN community is an aging population. The decline of the region’s fertility rates is due to a combination of barriers that work together to discourage child-bearing citizens from reproducing. The governments of ASEAN member states need to identify and offset these barriers and at the same time, embark on initiatives to develop institutional, economic and social innovations to improve their respective fertility rates.

Related articles: